By Andy Swenson

April 15, 2015

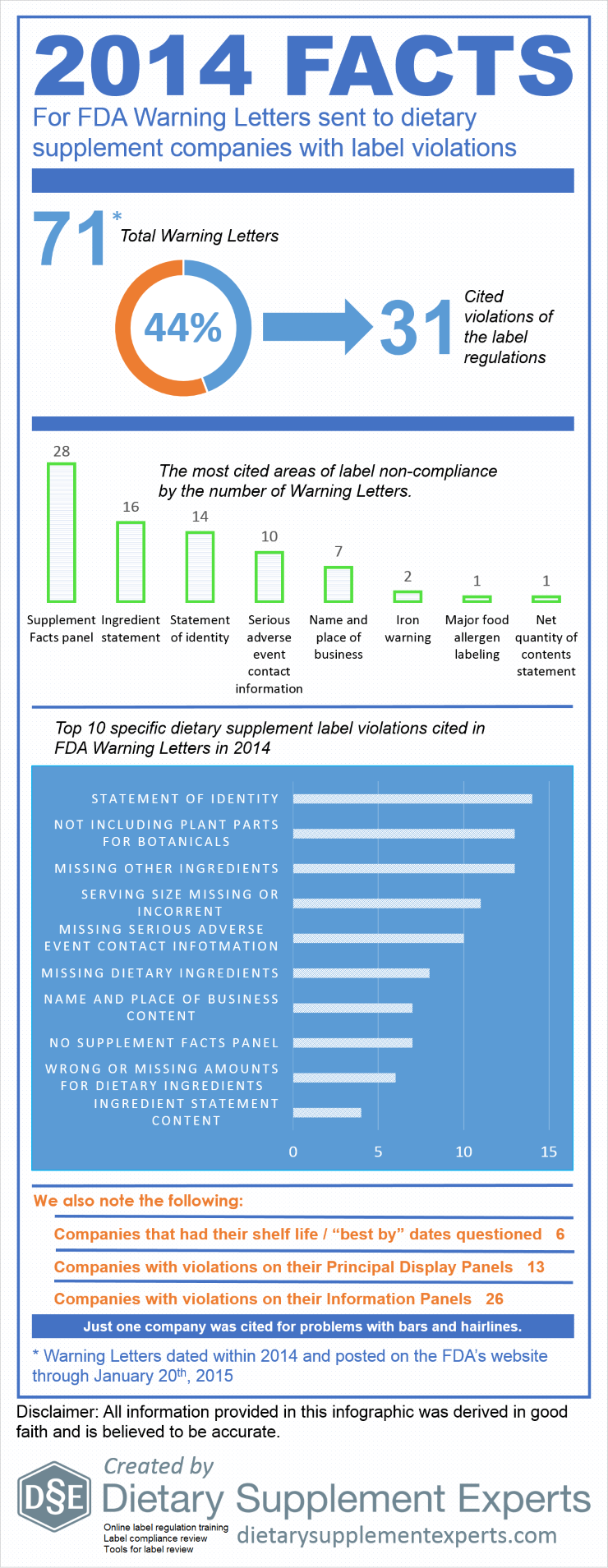

An observation commonly noted in FDA Warning Letters to dietary supplement companies is the use of a shelf life date, with an assumed lack of data which supports that date. At first glance this appears to be a legitimate requirement. However, when reviewing the Part 111 Final Rule and other statements made by the FDA, a conflict quickly arises.

An observation commonly noted in FDA Warning Letters to dietary supplement companies is the use of a shelf life date, with an assumed lack of data which supports that date. At first glance this appears to be a legitimate requirement. However, when reviewing the Part 111 Final Rule and other statements made by the FDA, a conflict quickly arises.

In the 21 CFR Part 111 Final Rule (72 FR 34751), published on June 25, 2007 the FDA responds to comments about shelf life dates by saying…

…any expiration date that you place on a product label (including a “best if used by” date) should be supported by data. (34856)

A simple internet search using the key words “Food Expiration Date” on the FDA’s website brings up the following:

Did you know that a store can sell food past the expiration date?

With the exception of infant formula, the laws that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) administers do not preclude the sale of food that is past the expiration date indicated on the label. FDA does not require food firms to place “expired by”, “use by” or “best before” dates on food products. This information is entirely at the discretion of the manufacturer.

And, from the Small Entity Compliance Guide, published in December, 2010:

Does the DS CGMP rule require me to establish an “expiration date” (or a “shelf date” or “best if used by” date)?

No. (72 FR 34752 at 34855)

It is important to recognize that neither shelf life dates for foods, nor data which supports a shelf life date is required. And, they are not mutually exclusive, i.e. you can have one without the other. This is evident for two reasons. Firstly, the Part 111 Final Rule and cGMPs define the word “Must” as a requirement. If data to support a shelf life date were required, “Must” (requirement) would be used instead of “Should” (which denotes a preference).

Secondly, the Part 111 cGMPs and FD&C Act do not explicitly state a company must have data which supports a product’s shelf life date. The only mention of shelf life dates is in reference to the length of time reserve samples must be held (111.83, 465 & 605). This is the reason shelf life date observations are always at the end of a warning letter and never included in the formal citations found in the body of the letter. The observation is an expectation which is different from an enforceable regulation.

Naturally, having a shelf life date supported by data is always preferred. However, companies are not required to meet FDA preferences, only the requirements stated in the Part 111 regulations and the distribution of safe product. If the FDA wants to require shelf life dates to be supported by data, then they must change the regulations.

A common practice within the Dietary Supplement industry is to manufacture a solid dose batch using a weight range of ± X%, where X equals the percentage over/under a Target weight (100%) and Target equals the minimum weight at which all of the label claim is delivered plus any amount added for shelf life overages. Some companies claim this practice yields misbranded product per the labeling regulations found in 21 CFR Part 101.9 because, statistically speaking, approximately half of the batch will be under 100% and all product which contain Class I nutrients must be at 100% of label claim. While this statement is true (half the batch would fall under 100%) it does not necessarily make the batch misbranded. This review will (i) provide a clear understanding of the sampling and testing methods used to verify label claims, (ii) provide a clear under-standing of what constitutes a misbranded product, and (iii) determine if using a weight range of 95% – 105% yields product that is suitable for distribution (not misbranded).

A common practice within the Dietary Supplement industry is to manufacture a solid dose batch using a weight range of ± X%, where X equals the percentage over/under a Target weight (100%) and Target equals the minimum weight at which all of the label claim is delivered plus any amount added for shelf life overages. Some companies claim this practice yields misbranded product per the labeling regulations found in 21 CFR Part 101.9 because, statistically speaking, approximately half of the batch will be under 100% and all product which contain Class I nutrients must be at 100% of label claim. While this statement is true (half the batch would fall under 100%) it does not necessarily make the batch misbranded. This review will (i) provide a clear understanding of the sampling and testing methods used to verify label claims, (ii) provide a clear under-standing of what constitutes a misbranded product, and (iii) determine if using a weight range of 95% – 105% yields product that is suitable for distribution (not misbranded).

If you are a frequent reviewer of dietary supplement labels, you have probably found that your speed and efficiency increase when you have your “tools” readily accessible. This month we have prepared a two-part series focusing on a selection of the important tools of our trade. If you are not currently using some of these, we help direct you to where you may find them.

If you are a frequent reviewer of dietary supplement labels, you have probably found that your speed and efficiency increase when you have your “tools” readily accessible. This month we have prepared a two-part series focusing on a selection of the important tools of our trade. If you are not currently using some of these, we help direct you to where you may find them.