By Curtis Walcker, M.S.

March 8, 2017

Four questions worth asking before participating in the Supplement OWL registry.

I review dietary supplement labels for clients on a near-daily basis – Sunday through Saturday – with very little exception. So in April of 2016, when I saw in the industry news that the Council for Responsible Nutrition (CRN) was launching its Supplement Online Wellness Library (Supplement OWL – http://www.supplementowl.org/index.html) label registry, I was interested. It did not appear to be something entirely different than the NIH’s existing Dietary Supplement Label Database (DSLD – https://dsld.nlm.nih.gov/dsld/).

Admittedly, after a brief read of a news article or two, I did not follow the developments very closely, other than to see it was in beta-testing with a handful of companies. However, this week advertising has ramped up significantly, and according to the site, the Supplement OWL is now accepting labels. As such, it seemed like a good time to try and weigh the risks and benefits of registering labels.

While some of the above sounds fine and possibly helpful, especially for consumers, I struggled to come up with really convincing reasons why I might want to register my labels as a brand owner. In fact, it was much easier to conjure up reasons that registering might not be a good idea at all. Here are four questions worth asking before participating in the registry:

- Will my customers find my products in the registry and gain trust in them?

A lot of things have to line up for this to work out. First, your customers will need to learn about what the Supplement OWL is. Then they have to take the time to use it. And even if they use it, they then need to know how to take the information provided by the registry and interpret it well enough to make informed buying decisions. All of which may not give the slightest guarantee that a product is free of adulterants or manufactured under cGMPs. Will consumers seek out only registered label products? That seems unlikely, but more likely in a scenario where retailers demand registration.

- Do I really want to make my labels and information available to the FDA and FTC more than I already do?

The only public comment from the FDA that is readily found in a NutraIngredients-USA article basically states that the FDA looks forward to learning more about the program, but will continue to focus on compliance throughout the industry. That does not indicate strongly that the FDA would be spending time looking through the registry. However, if the FDA decided that a widely used ingredient was not a legal dietary ingredient for instance, the registry could be used to identify offenders – which is great, unless you might be an unassuming offender. On the FTC side, it is imaginable that they could search out products for something like brain health, and you might end up under more scrutiny than you otherwise might have.

- Who else might be looking?

This is the real question to ask. The Supplement OWL could become a treasure trove to enterprising plaintiffs’ attorneys seeking out product labels with improper Made in the USA claims, arguable natural claims, FALCPA non-compliances, claims questionable in regards to substantiation, and more. Just like they are said to patrol the FDA Warning Letters, a registry with so much information could also open up more doors for these frivolous occurrences.

- How much time will it take to participate?

If you are a brand owner with many labels, it could be a large amount of upfront work, as well as maintenance work. There is a lot of data to enter with each product, and if you have been in the industry any amount of time, you will know that label revisions are made frequently for address changes, excipient changes, ingredient changes, not to mention all of the new Supplement Facts panels that will come in to effect in the not so distant future. The information you enter today could be obsolete tomorrow. You should be prepared to commit significant time to not have outdated information floating around out there.

The above questions and concerns are purely speculative at the moment, but as a brand owner, I think my strategy right now would simply be to wait and see how everything plays out over the next year or so. If you are a CRN member, that might not be an option, as participation appears to be mandatory. However, if you have the luxury of taking it slow, you might keep close watch, and even try to identify some leverage points from the outside, such as more easily monitoring competitor products and surveying entire product categories.

On May 20, 2016, the FDA announced that it has finalized new rules that will make significant changes to nutrition labeling for the first time in more than 20 years. The two final rules that the FDA is issuing pertain to food and supplement labeling as well as a rule that will amend reference amounts customarily consumed (RACCs) and regulations around serving sizes. These changes are made to help consumers make better informed decisions about the food they eat.

On May 20, 2016, the FDA announced that it has finalized new rules that will make significant changes to nutrition labeling for the first time in more than 20 years. The two final rules that the FDA is issuing pertain to food and supplement labeling as well as a rule that will amend reference amounts customarily consumed (RACCs) and regulations around serving sizes. These changes are made to help consumers make better informed decisions about the food they eat.

Communicating the features and benefits of your dietary supplements is a critical success factor. Although this can be done in several ways, the most powerful is usually through the use of structure/function claims. A common misnomer about these claims is that virtually anything can be said as long as the FDA disclaimer language is added to the label or labeling. Unfortunately, this is far from the truth. There are regulations that put significant limitations on what can be said, and it is truly an art to not only saying things compliantly, but also in ways that are meaningful to consumers. Here are some of the most basic aspects of structure/function claims.

Communicating the features and benefits of your dietary supplements is a critical success factor. Although this can be done in several ways, the most powerful is usually through the use of structure/function claims. A common misnomer about these claims is that virtually anything can be said as long as the FDA disclaimer language is added to the label or labeling. Unfortunately, this is far from the truth. There are regulations that put significant limitations on what can be said, and it is truly an art to not only saying things compliantly, but also in ways that are meaningful to consumers. Here are some of the most basic aspects of structure/function claims.

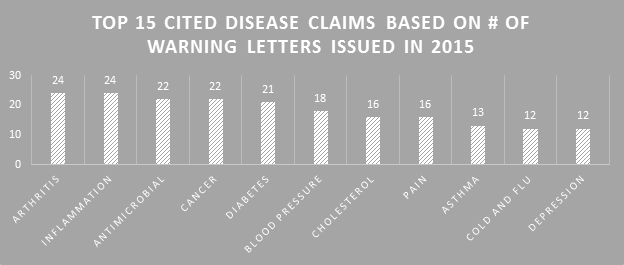

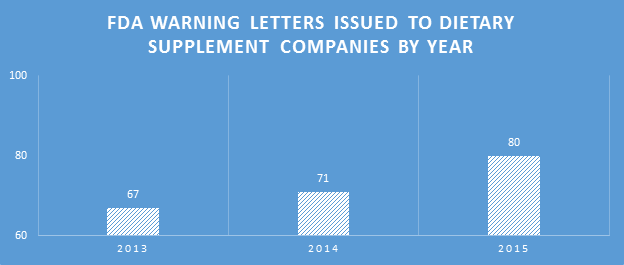

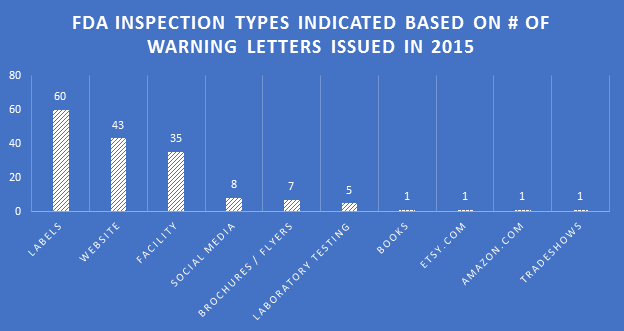

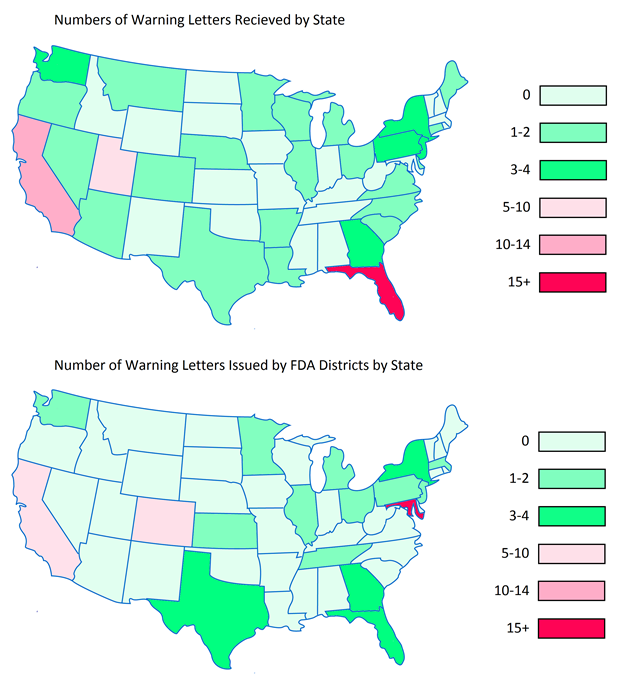

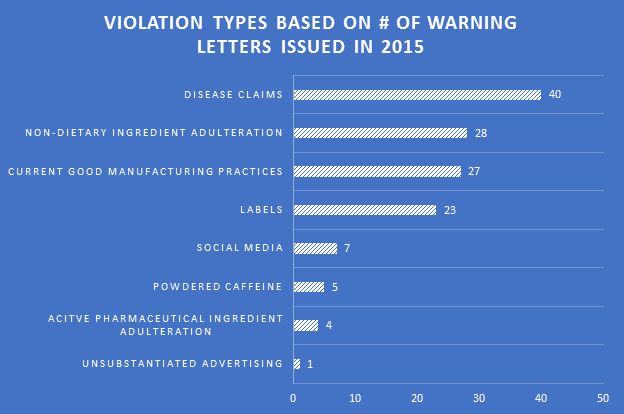

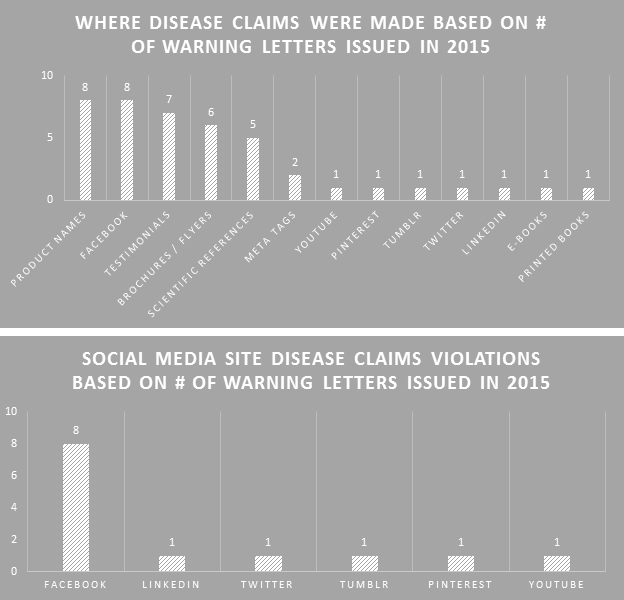

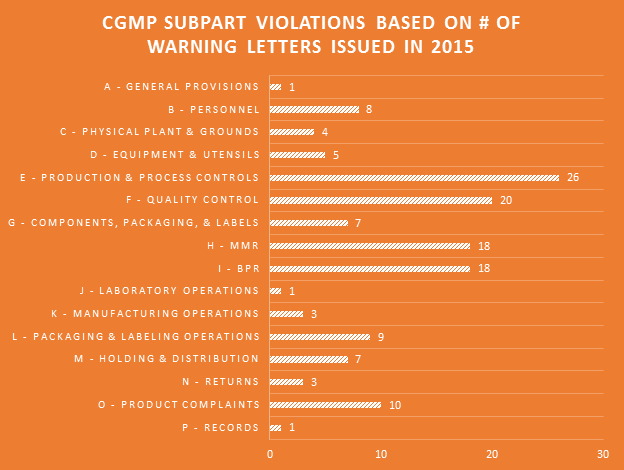

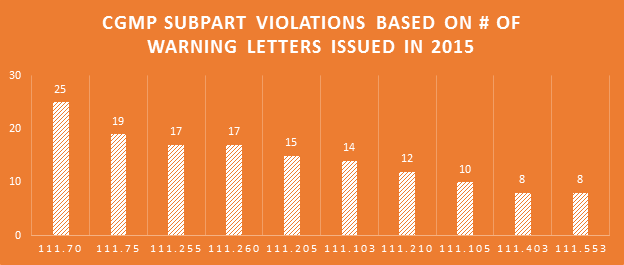

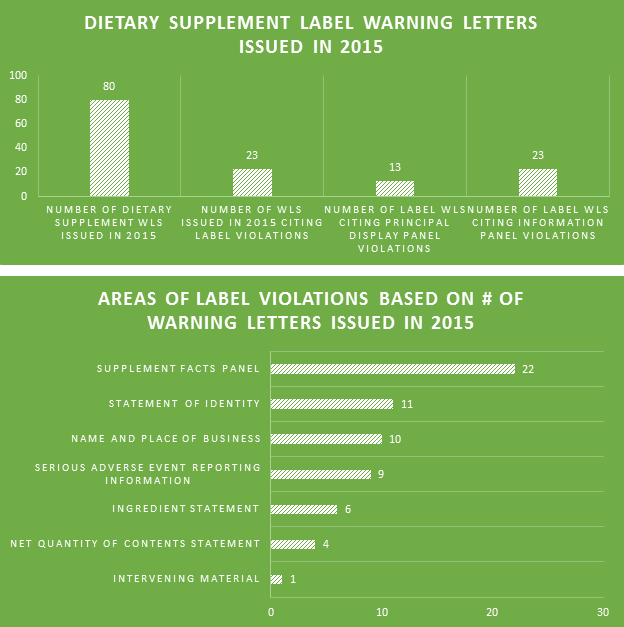

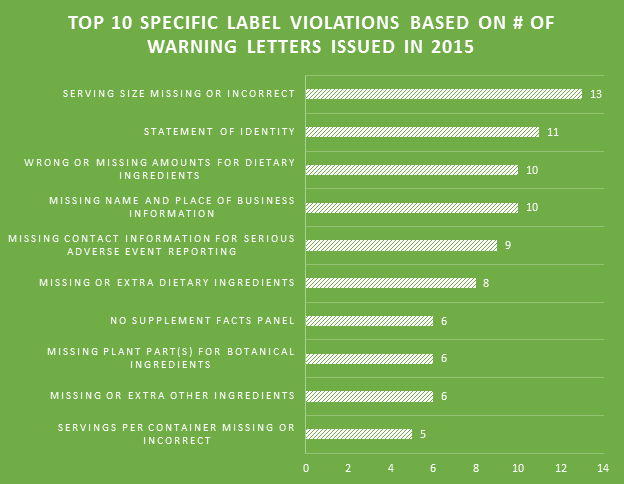

Many professions require continuing education to keep the professionals in those fields abreast of the trends and evolving research. For us that are involved in dietary supplement regulatory affairs, one of the best unofficial methods of continuing education comes in the form of FDA Warning Letters. A careful reading of these each week not only reminds us of the regulations, but shows us how the FDA is interpreting them, and which issues might be on their radar. In addition, when we are suggesting that our companies or client’s make changes to their manufacturing practices, labels, claims, etc., it can be easier at times to get buy-in when not only the regulations, but also one or more recent FDA Warning Letters can be brought to the discussion table to demonstrate the needs and the associated risks.

Many professions require continuing education to keep the professionals in those fields abreast of the trends and evolving research. For us that are involved in dietary supplement regulatory affairs, one of the best unofficial methods of continuing education comes in the form of FDA Warning Letters. A careful reading of these each week not only reminds us of the regulations, but shows us how the FDA is interpreting them, and which issues might be on their radar. In addition, when we are suggesting that our companies or client’s make changes to their manufacturing practices, labels, claims, etc., it can be easier at times to get buy-in when not only the regulations, but also one or more recent FDA Warning Letters can be brought to the discussion table to demonstrate the needs and the associated risks.

This month’s article highlights five mistakes in label compliance that we commonly see in our dietary supplement label reviews.

This month’s article highlights five mistakes in label compliance that we commonly see in our dietary supplement label reviews.

If you are currently using “Made in USA” claims, either explicitly or by implication with the use of images such as the U.S. flag or map, it might be a good time to review them. Recently, a number of companies have been targeted in California-based lawsuits for non-compliance and potentially misleading consumers.

If you are currently using “Made in USA” claims, either explicitly or by implication with the use of images such as the U.S. flag or map, it might be a good time to review them. Recently, a number of companies have been targeted in California-based lawsuits for non-compliance and potentially misleading consumers.

The FDA posted a new Warning Letter on their site today. The recipient was Yummy Earth Inc., located in New Jersey. It was instantly interesting because this is the second week in a row that the FDA has cited violations for misusing “healthy” nutrient content claims. This new beginning trend started with last week’s letter to KIND, LLC, which has received a considerable amount of attention in the press.

The FDA posted a new Warning Letter on their site today. The recipient was Yummy Earth Inc., located in New Jersey. It was instantly interesting because this is the second week in a row that the FDA has cited violations for misusing “healthy” nutrient content claims. This new beginning trend started with last week’s letter to KIND, LLC, which has received a considerable amount of attention in the press.